|

|

|

Friday 03 June 2005

Customer Service

How Not To Do It: Customer Service In An Age Of Fraud Apple’s .Mac service says they want me back, but they have a funny way of showing it.  I like to consider that I’m a pretty savvy person, without being paranoid. I’ve been abused of a couple of times by sleazy online merchants, but I’ve never actually been ripped off, nor have I ever been the victim of ‘identity theft’. I have never used any anti-virus software on Windows, and yet I have never actually had a virus infection on any of my computers. If you pay just a little bit of attention, you can get through life mostly unscathed. On Tuesday, though, I was very busy: I was up to my ears in work, and literally talking on two phones at once like a tycoon in an old movie: ‘Buy Steel!’ ‘Sell Radio!’ ‘Get Wilkins in here with the Schenectady numbers!’ etc. While all this tycooning was going on, my cell phone rang with ‘Unknown’ showing on the caller ID. I’m now on three phones at once. The guy on the other end said that he was Steve, from Apple Computer, and he asked whether I’d like to renew my recently-expired trial .Mac account. It’s hard to explain just what .Mac is; mainly, it’s a scheme by which Apple can get $99 a year out of you. For your money you get an e-mail account, space on a web server, private online storage space for your files, and a few other things. It’s actually a good deal if you make use of all of it: as it is, I need almost none of this. I already have my own e-mail and web server, and over a terabyte of on-line storage in the basement. A few features, though, are difficult to duplicate. Macintoshes come with a program called iSync, which is superficially a utility to sync your phone or your PDA with the information on your computer. iSync also can sync the information on multiple computers, which is what I’m interested in. I have a laptop and a desktop computer, and I use them pretty interchangeably. The challenge is keeping the web browser bookmarks, address books, an calendars on each machine in sync. With some programs, this wouldn’t be a problem: you could just send files around. Apple’s Safari web browser, Address Book, and iCal programs — which I use because they don’t annoy me, which is something like high praise — deliberately make this difficult, because Apple wants that $99 a year. It’s hard to do unless you pay $99 a year to use all of iSync’s features, in which case it becomes incredibly easy. Apple’s products are of such a high quality, and please their users so much, that Apple can afford to occasionally throw a monkey wrench like this into the experience. After all, what am I going to do if I don’t like it? Use Windows or Linux on the desktop? In order to save $99 a year, I’m going to screw around with Windows? I hardly think so. So I got a free 60-day trial of .Mac when I bought my most recent computer, and the time had come either to pay or to give it up. I hadn’t made a decision. Until that guy called on the phone, that is. What the hell, I’d renew. But I asked: is there any advantage to renewing with the phone solicitor rather than online? I’d get three times the on-line storage (1 GB vs. 250 MB), he said. I don’t consider that much of a bonus — 25% off the price would be a bonus — but all right, fine, I’ll pay. I had tired of trying to roll my own .Mac. I gave the guy my credit card number, the (mis)spelling of my name as it appears on the card, and my billing address. He then told me that the charge would appear on my card as ‘Apple Computer’, that a confirmation e-mail would be sent to my .Mac e-mail address, and that tomorrow afternoon — that is, Wednesday — I should log in to the .Mac service via the mac.com web site, and that my password would be changed to ‘password’ to facilitate this. After I’d got off all the phone calls, I thought about this for a while. It smelled fishy. To begin with, why on earth would this process take more than 24 hours? And why should it involve resetting my password, particularly to something so predictable? I already had a password; all they’d have to do is set my account status to ‘active’ after charging my card. And why on earth would they send a confirmation e-mail to an address that I wouldn’t have access to unless the transaction succeeded? I can think of plausible answers for all of these questions that don’t involve attempted fraud, but I can also think of plausible answers that do involve fraud. So I had just given my credit-card details to someone based solely on the fact that he knew three things:

Further, Apple’s own .Mac privacy policy says ‘Apple will not contact you or share your information unless you authorize it’. Now by this they probably mean that they won’t subject me to endless phone spam attempting to sell me other stuff, but the policy doesn’t say that. The policy says ‘Apple will not contact you’, and here was someone representing himself as being from Apple, contacting me. I tried to find some way to contact Apple about this, but the only way to contact the .Mac people in any way appears to be a web form here. They say that their ‘service experts’ will ‘make every effort to reply’ within 48 hours. I filled out the form, asking whether they actually used phone solicitors to sell account renewals. For good measure, I then called my bank and cancelled my credit card. The next afternoon (Wednesday), my cell phone rang again with an ‘Unknown’ caller ID. I answered, and sure enough, it was ‘Steve’ with Apple again. He said that the credit card number I’d given him had been declined, and did I have another one they could use? I mean, those were very nearly his exact words. I asked him whether there was a phone number at which I could call him back, and he gave me 1-800-385-5172, extension 535. This phone number does not turn up in Google (or at least it won’t until I post this). I called this number and was met with a recording that said hello from Apple, and said that I should enter an extension number or stay on the line. I stayed on the line, and a few seconds later was talking to a woman who’d answered the phone with something akin to ‘.Mac customer support’. I asked for extension 535, and in a couple seconds I was talking to Steve again. I then laid out the story for him. I apologized for essentially accusing him of being a scam artist, and said that the whole situation seemed suspect to me, and that I had cancelled the credit card. I specifically mentioned the extreme fishiness of resetting my password to ‘password’; he defended this practice by saying ‘that’s what we do for everyone’. This is hardly reassuring, to say the least. If you forget your login password for Apple’s online discussion boards there’s better security. Steve was pretty defensive in general. If he was a scam artist, he asked, how would he know my mother’s maiden name? He told me my mother’s maiden name for verification. I told him that had there been a data security breach at .Mac, all of this information could be readily available to him (and that the mother’s-maiden-name thing is hardly secure anyway). I told him that I could think of no simple way that he could convince me of his legitimacy, and that given the thing with resetting the password to ‘password’, that I wasn’t sure I wanted to have anything to do with .Mac even if he was legitimate. I then wished him a nice day and we parted ways. On Thursday at 2:51 p.m., I got an e-mail in response from my online .Mac support query. My exact query to them was:

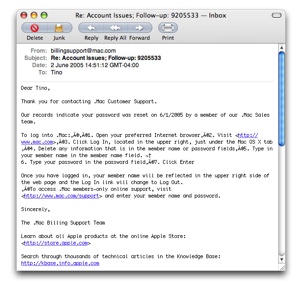

I have to present their response to me as a graphic, instead of text. Click on the picture for a bigger version.  The headers on this message show that it originated with a computer calling itself snowy.corp.apple.com with an IP address of 17.254.13.36. All IP addresses beginning with 17. are in Apple’s address space, so this probably comes from within an Apple network. (This address actually resolves back to A17-34-112-122.apple.com, not snowy.corp; but that’s not unusual.) Interestingly, the e-mail headers seem to indicate that that computer is running AIX, which is to say IBM Unix. Apple doesn’t eat its own dog food. So anyway, while the message is probably legitimate, it hardly inspires confidence, what with its strange line breaks and odd high-ASCII garbage (this is how the message displays in Apple’s own Mail.app program, so claims of character set incompatibilities and so forth will hold no water). In fact, if I didn’t know how to read e-mail headers, this message would have absolutely convinced me that I was being set up. So this phone-sales guy Steve was probably on the level, and I’ve gone through the hassle of canceling that credit card for nothing. But I think that this experience occasions the establishment of an annex to the Customer Service Rules, specifically for these kinds of situations. If you are in a position of ever calling customers and asking them for information:

And finally, less of a customer-service rule than a general guideline for everyone: never, ever, ever set a password to ‘password’. I mean, really now. Not only do you make yourself look silly by even suggesting such a thing, but you set yourself up for sabotage and, if you’re doing it for your customer (as opposed to for your own account), liability. Let’s assume for a moment that Steve is a totally legitimate Apple sales guy. Let’s also assume that Steve, or someone like him, develops some sort of animosity toward Apple. After he reset a password to ‘password’, all he’d have to do is communicate the account name to a friend of his, who could go in and replace all the existing data with goatse pictures. There’s been a lot of online-commerce punditry to the effect that the Internet levels the playing field: Joe’s Cheese Emporium can, if Joe is adept with HTML and a database, ‘look just like’ the web premises of a far larger company. This is a good thing. But Jimmy The Grifter’s Online Scam Hut can also ‘look just like’ — a lot more like, in fact — a much larger and more trusted company. In the past, Jimmy The Grifter would have had to rent space, furnish it, and spend a whole lot of money on other things in order to rip people off by fooling them into thinking they were dealing with someone else. Today, it’s trivial to pull the same scam online or over the phone. Companies in the industrial age worked to establish and defend their brand names and trademarks against impostors. Today it’s important to establish and defend your entire corporate identity, and to make sure that every single thing you do can be at least reasonably authoritatively tied back to that identity by your customers. Either you spend the money to do this now, or you spend the money later, after some public-relations disaster, trying to convince people that they can deal with your company in confidence. Posted by tino at 14:25 3.06.05This entry's TrackBack URL::

http://tinotopia.com/cgi-bin/mt3/tinotopia-tb.pl/433 Links to weblogs that reference 'How Not To Do It: Customer Service In An Age Of Fraud' from Tinotopia. Comments

During my ordeal with apple support to get an order I placed that had UPS shipping issues. I encountered that character set problem that you noted. It is fairly obvious that Apple outsourced support but lets that firm use their local character set in email correspondence to US customers. I also found that they (along with other email support outfits) don’t always answer your question but rather cut and paste from a FAQ or some ‘knowledge base’ for what they think solves your probloem. Posted by: Paul at June 6, 2005 08:00 AM |